HISTORY OF HUMOUR IN CINEMA

by

DONALD DEWEY

_______________

Don

Dewey has published 25 books of fiction, non-fiction and drama,

including Marcello Mastroianni: His Life and Art, James

Stewart: a Biography and The

Art of Ill Will: The Story of American Political Cartoons.

The

setting can be an elegant restaurant, an over-furbished library,

or a dank cellar. Present are one American and one or more

foreigners. The foreigner wants something of value from the

American --- an object, a piece of information, some other

concession. He is willing to be polite about getting it, but

a threat in the air suggests he has no objection to resorting

to violence for his purposes, either. The American tries to

disguise his discomfort by cracking wise about the foreigner’s

persistence --- upon which the foreigner, whether born in

Hamburg, schooled in Algiers, or married in Kuala Lumpur,

will utter the immortal line: “Zat most be ze famus

Amerikan senz off yamur.”

The

famous American sense of humour. It is a national trait that

Americans have had ascribed to them on movie screens for decades.

The chest expands before the compliment. Along with loving

children and being kind to animals, being recognized for a

sense of humour forms the holy trinity of reassurances sought

by any culture that deems itself humane and enlightened. Who

would want to deny having a sense of humour? Godliness and

cleanliness pale next to it.

The

famous American sense of humour. It is a national trait that

Americans have had ascribed to them on movie screens for decades.

The chest expands before the compliment. Along with loving

children and being kind to animals, being recognized for a

sense of humour forms the holy trinity of reassurances sought

by any culture that deems itself humane and enlightened. Who

would want to deny having a sense of humour? Godliness and

cleanliness pale next to it.

But

wait. What American sense of humor? George Washington’s?

George Carlin’s? That of George W. Bush’s speechwriters?

What George are we talking about here? And since when has

it been so famous? Did I miss those high school history classes

that would have told me how much of a cutup George Custer

had been at the Little Big Horn? Conversely, have I been completely

imagining those bookstore shelves filled with collections

of French bon mots, Czech ironies and Irish outlandishness?

Some of the material in them goes back centuries, doesn’t

it? When did Europeans, especially, become good only for an

occasionally sardonic expression of a keenly felt smugness

(that made them calculating, not comical)? Just exactly when

did the United States win not just World War I, World War

II, the Race to the Moon War, the Grenada Dental School War,

the Cold War, the Miniature Gulf War, and the Halliburton

War, but also the Funny War? From what private stock of chauvinist

spirits have those generations of California screenwriters

been drinking?

One

clue is that word “famous.” Remember the last

time we heard it -- for describing those Page Six and “Entertainment

Tonight” party-goers who were famous because they were

famous? Could this be another example of that media rush we

have come to embrace as cultural attribute, the alternative

being that gloomy feeling of being left out, left behind and

left at the curb? As we know, the only thing worse than being

accused of lacking a sense of humour is being oblivious to

lacking it.

A second clue is the medium -- motion pictures -- that has

done so much to propagandize our humour superiority as fact.

That line about the famous sense of humour became boilerplate

more or less in the 1930s, the period when the Grants, Hepburns

and Astaires were sweeping through the suave, the brilliant

and the zany. To read some film histories, that marked the

coming of age of screen comedy -- and it didn’t happen

in Bucharest. Nor did it happen on a theatre stage where only

a few hundred people could appreciate it. The movies were

critical not only for making the humour cultural claim for

Americans, but for making it around the world three or four

shows daily to millions.  When

the projector spoke, we listened, relishing the thought that

audiences in lederhosen and saris were hearing the same announcement

in their villages. If they accepted us as the most humourous

people on earth, who were we to object?

When

the projector spoke, we listened, relishing the thought that

audiences in lederhosen and saris were hearing the same announcement

in their villages. If they accepted us as the most humourous

people on earth, who were we to object?

Who

are we to object even now? However pretentious, what harm

can such a claim do? Saying we have a famous sense of humour

is hardly as ominous as saying we have a famous sense of habeas

corpus; just because that boast served as the prelude to ugly

contradictions doesn’t mean we’re all soon going

to be banning jokes as a security measure against terrorism.

Saying we have a famous sense of humour might be vain typology,

but that doesn’t make it lethal to non-Americans taking

us at our word, does it? Aren’t we entitled to a small

illusion of homeland security?

Sure

we are -- provided we forget about history. And that’s

led to serious problems before.

Since

motion pictures have been so instrumental in illuminating

our humour chromosomes, let’s start with their history.

By now it is practically a military secret that in its earliest

days film humour was very much a European province. The grandfather

of all movie laughter was Louis

Lumiere’s L’Arroseur arrosée,

an 1897 French short that depicts a jaunty gardener watering

his lawn, a boy sneaking up to step on the hose, the surprised

gardener examining the nozzle of the hose to see what’s

wrong, and the boy immediately stepping off the hose again

to soak his victim. Thomas Edison was so taken with L’Arroseur

arrosée that he copied it for his 1898 one-reeler “Washday

Troubles,” bothering only to substitute a tub of soapy

water for the hose.

Since

motion pictures have been so instrumental in illuminating

our humour chromosomes, let’s start with their history.

By now it is practically a military secret that in its earliest

days film humour was very much a European province. The grandfather

of all movie laughter was Louis

Lumiere’s L’Arroseur arrosée,

an 1897 French short that depicts a jaunty gardener watering

his lawn, a boy sneaking up to step on the hose, the surprised

gardener examining the nozzle of the hose to see what’s

wrong, and the boy immediately stepping off the hose again

to soak his victim. Thomas Edison was so taken with L’Arroseur

arrosée that he copied it for his 1898 one-reeler “Washday

Troubles,” bothering only to substitute a tub of soapy

water for the hose.

France’s

other great film pioneer, George

Melies, was first of all a comic satirist, specializing

in technical gags that reflected his earlier career as a professional

magician. His 1899 piece, The Conjuror, is a flashy series

of vanishing acts and physical displacements aimed at laughs.

And only the reverence accorded the 1902 fantasy A Trip to

the Moon for its influence on the film medium as a whole obscures

the parodies at the heart of Melies’s treatment of many

of its characters. Most seminal of all in the evolution of

cinema humour was yet another Frenchman, Max Linder (Gabriel-Maximilien

Leuvielle), whose dandy lay-about character polished film

slapstick, established him as the world’s leading comedian

up to World War I, and served as an inspiration for Mack Sennett

and Charlie Chaplin.

Other

European countries were not too far behind France in going

for the funny bone; indeed, the only conspicuous exception

between the turn of the 20th century and World War I was Russia,

where the Czar clamped an iron hand over any film project

that failed to celebrate the Romanovs or great patriotic figures. In Germany, Oskar Messner starred in a number of risqué

comedies that were popular not only in his own country and

around Europe, but also in the

United States. Long before he had gained a reputation as a

masterful director of sophisticated comedy, Ernst Lubitsch

had developed a following on the continent for a series of

comic shorts in which he played a German bumpkin named Meyer.

Around the same time in Sweden, Mauritz

Stiller was crafting a Scandinavian genre of

ironic comedy, but not so preciously that there wasn’t

room for scores of pratfalls and various other visual gags

in works like The Modern Suffragette (1913) and When the Mother-in-Law

Reigns (1914).

In Germany, Oskar Messner starred in a number of risqué

comedies that were popular not only in his own country and

around Europe, but also in the

United States. Long before he had gained a reputation as a

masterful director of sophisticated comedy, Ernst Lubitsch

had developed a following on the continent for a series of

comic shorts in which he played a German bumpkin named Meyer.

Around the same time in Sweden, Mauritz

Stiller was crafting a Scandinavian genre of

ironic comedy, but not so preciously that there wasn’t

room for scores of pratfalls and various other visual gags

in works like The Modern Suffragette (1913) and When the Mother-in-Law

Reigns (1914).

In

London, Robert

Paul, the first exhibitor of British

films to a paying public, began turning out comic shorts before

the turn of the century with the confidence that they would

be his most profitable source of income. One of the most technically

elaborate and financially successful of all British films

before World War I was A Suffragette in Spite of Himself (1912),

a revival of the pranksterism from Lumiere’s L’Arroseur

arrosée in its tale of an obnoxious male chauvinist

who walks around London unaware that teenagers have stuck

a pro-feminist declaration on the back of his coat. Comedies

were also a film staple in Denmark, Italy and Hungary.

In

London, Robert

Paul, the first exhibitor of British

films to a paying public, began turning out comic shorts before

the turn of the century with the confidence that they would

be his most profitable source of income. One of the most technically

elaborate and financially successful of all British films

before World War I was A Suffragette in Spite of Himself (1912),

a revival of the pranksterism from Lumiere’s L’Arroseur

arrosée in its tale of an obnoxious male chauvinist

who walks around London unaware that teenagers have stuck

a pro-feminist declaration on the back of his coat. Comedies

were also a film staple in Denmark, Italy and Hungary.

The

genre continued to rule throughout Europe’s silent film

era. As box office receipts on both shores of the Atlantic

confirmed, foibles were foibles, and exposing them, exaggerating

them and enjoying them were pastimes without borders. But

then came sound, and the predilection by movie makers to hang

more of their humour on dialogue. What was funny grew vulnerable

to extra-national translation problems that were not always

resolved happily; i.e., verbal idiosyncrasies hilarious in

Italy might only perplex audiences in the Netherlands dependent

on approximate subtitles or syllable-conscious dubbing. Moreover,

the very prospect of foreign verbal comedy could daunt audiences

in a way imported dramas, action adventures and mysteries

did not because it called for an ongoing, expressive participation

from the spectator known as laughter. It didn’t really

matter whether the absence of that laughter was due to the

original film, inept subtitling or dubbing, or the obtuseness

of the viewer in the orchestra; the main thing was that audiences

expected to laugh that didn’t laugh were very uncomfortable

audiences, and uncomfortable audiences were unlikely to expose

themselves to a potentially disagreeable situation a second

time. The upshot was that, lacking a major star to assure

long lines outside the cashier’s booth in both Lisbon

and Warsaw, comedies became the least desirable film genre

in Europe in the first decade of sound.

If

American studios experienced fewer problems on the continent,

it was largely because of their control of European distribution

networks and block booking: To get Greta Garbo, Switzerland

also had to take some B comedy about Nebraska wheat growers

and make the best of all those jokes about Lou Gehrig. But

even in this monopolistic context it soon became evident that

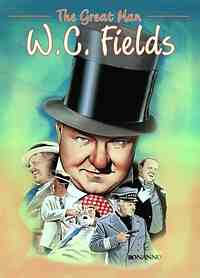

some very important figures in American screen humour -- Will

Rogers, W.C. Fields, Philip Barry, S.J. Perelman and George

S. Kaufman, to name just five -- did not travel well in Europe.

(Although somewhat more popular, Groucho Marx would have to

wait years for his work to gain recognition as more than an

appendage to Harpo’s antics or even to his own makeup).

At the same time, in a market already restricted to a handful

of foreign imports every year, European comedies of the 1930s

found little of the enthusiasm in the U.S. that had welcomed

Max Linder and Oskar Messner. Whether it was Rene Clair’s

A Nous la Liberté (1931) or even a British comedy such

as J.B. Priestley’s The Good Companions (1933), satire

was still something that closed on Saturday night.

Of

course, European film comedy in the 1930s was up against more

than the problems posed by sound and block booking. In Germany

there was Adolf Hitler, in Italy there was Benito Mussolini

and in the Soviet Union there was Joseph Stalin. Spain went

through two upheavals to end up with Francisco Franco, and

the entire continent staggered under an economic depression.

If European film makers concluded there was not too much to

laugh at, they could be forgiven their grasp of reality. If

they decided that attempts by the continent’s various

dictators to encourage more comedies in order to generate

an illusory sense of national well-being defined whistling

in the dark, they could be equally pardoned. Genuine laughs

simply didn’t come easily in the Europe of the 1930s.

Nevertheless,

it was a giant leap from the perception that nationally flavoured

comedies reliant on dialogue humour from severely tested countries

were not so exportable to the view, rampant in Hollywood films

from the early 1930s, that the only good European was a humourless

European. That judgment required considerable reaching, starting

with the need to ignore the European comedies the American

industry knew were out there along with the latest grim Fritz

Lang masterwork. Paradoxically, it required Americans to take

themselves more seriously; i.e., to be more consciously ideological.

It also required absolute denial that this was what was going

on.

The first public figure recorded as using the word ‘ideology’

disparagingly was Napoleon, when he shrugged off French philosophers

opposed to his imperial ambitions as “mere ideologues.”

Gradually, the word degenerated into a synonym for everything

from inert intellectualism and overripe theorizing to dogma

and outright lie. Outside academe, few held to the term’s

fundamental meaning as a would-be total view of human activity

and purpose enlisting the dynamics of intellectual speculation,

idealistic belief and social arrangement. Fewer still were

those who, not hypnotized by the neat schematics of their

own worldview, acknowledged the constant shifts of perspective

necessitated by evolving realities and envisioned by French

philosopher DeStutt de Tracy when he proposed ideology as

a new science of ideas at the beginning of the 19th century.

When ideology didn’t invite rejection for being its

own worst ism, in other words, it was ridiculed or dismissed

for parenting harmful offspring.

Sometimes

the children haven’t even had to seem menacing to be

spurned. One striking feature of American skepticism toward

isms is that, while most often explicitly addressed to the

aspirations embodied in European anarchism, fascism and communism,

it has also been close to the surface in attitudes toward

the ideological contents of the French Revolution and even

those of the American Revolution. A review of the U.S. mass

media’s understanding of the French Revolution over

the years, for example, would disclose little more than a

social eruption that began in the best of times and worst

of times and that ended with some people doing a far, far

better thing than they had ever done before -- if only because

the Scarlet Pimpernel couldn’t save them in time. At

home, once having dispensed with terms like freedom and independence,

we appear to have exhausted our interest in the social and

political substance of the American Revolution. Certainly,

it has been less taxing to dwell on the image of a colonial

rebellion rather than on that of a revolution proper, since

this has allowed us to regard ourselves as emotional, instinctual

and ultimately responsive only to what any aggrieved innocent

would have been responsive to in such oppressive circumstances.

Has

it been mere coincidence within this anti-intellectual tradition

that the entertainment media’s treatment of the American

Revolution has, after the singing and hoofing of 1776, mostly

started and stopped with television serials adapted from mass

paperback romances and best-selling biographies? Doubtlessly

assisted by the calculation that enemies who sport powdered

wigs and fire one-shot muskets aren’t anywhere near

as enthralling in trailers as unkempt rebels charging down

a hill and blazing away with Colt .45s, Hollywood (but also

Publishers Row and other hubs of public fantasy) has tended

to take D.W. Griffith at his word that the Civil War, not

the War of Independence, marked the birth of the nation. And

of course the true values of that conflict, as we have been

told since grammar school, were simplicity itself: no secession

and no slavery, hallowed propositions requiring no more thought

than that needed for espousing freedom and independence.

But

the scarcity of persuasive fictional portrayals of the American

Revolution has not prevented film makers from attempting to

define the American character or the values supposedly shaping

it; on the contrary, once moved to a safer (more commercial)

contemporary setting, that task has been a preoccupation of

reflective film makers since -- wouldn’t you know it?

-- the 1930s. Even today a poll asking where American social

and cultural beliefs have found their clearest and most potent

cinematic expression would yield as a popular answer Frank

Capra’s Everyman pictures in the 1930s

and 1940s, when Mr. Smith went to Washington and Mr. Deeds

dropped in on the town. And what exactly were the values advocated by Capra through

his James Stewart and Gary Cooper heroes even as they both

were deluged by seas of cynicism? Honesty, for one. The rewards

and satisfactions to be gained from hard work, for a second.

The democratic right to happiness, for a third. In other words,

no principle normally thought of as -ismic; indeed, nothing

that required any of that book learnin’ at all. As Mr.

Smith made clear during his filibuster, the only modern text

worth paying attention to was the Constitution; as Mr. Deeds

demonstrated, the only honest writing was to be found in the

doggerel of greeting cards -- a tip of the hat to the Bible

for having inspired the best sentiments of both.

And what exactly were the values advocated by Capra through

his James Stewart and Gary Cooper heroes even as they both

were deluged by seas of cynicism? Honesty, for one. The rewards

and satisfactions to be gained from hard work, for a second.

The democratic right to happiness, for a third. In other words,

no principle normally thought of as -ismic; indeed, nothing

that required any of that book learnin’ at all. As Mr.

Smith made clear during his filibuster, the only modern text

worth paying attention to was the Constitution; as Mr. Deeds

demonstrated, the only honest writing was to be found in the

doggerel of greeting cards -- a tip of the hat to the Bible

for having inspired the best sentiments of both.

As

the scores of Hollywood films unspooled after Smith and Deeds

argued repeatedly, these core values had absolutely nothing

in common with the ideologies that had taken root in Europe

in the 19th and 20th centuries, neither in content nor in

form. For openers, the European ideologies would have been

inconceivable without their elaboration and argumentation

in books and periodicals -- suspect intellectual arenas to

congressmen and jingle writers. To one level of sophistication

or another, anarchism, fascism, and communism (the three most

prominent isms) were programmatic philosophies that proposed

specific steps to reach specific objectives. In their realization,

action was stipulative, not instinctive; was predicated on

theoretical as much as social achievement. Even those not

sharing the European ideology in question were directly relevant

to its embrace as active or potential foes, as part of the

problem when not of the solution. From ideology’s viewpoint,

everybody was involved.

But

despite its proud impatience with the European isms, the ideology

known as the “American way of life” has also had

its own all-inclusiveness. If only species of the lunatic

fringe have actually gone around talking about ‘Americanism’

as some philosophically delineated vision, there has remained

a much vaster consensus around the conviction that personal

ambition, agility and spontaneity animate capitalism with

a human face, and that this too includes everybody, successfully

or not, like it or not. At no time was this belief more visibly

urgent than in the 1930s, when the depression had wiped the

humanity off capitalism’s face and the ideologies from

abroad were doing all that infamous creeping into American

society. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called on

Hollywood to help the country through the depression (and,

later, through World War II), he wasn’t talking only

about the gangster films Warner Brothers was churning out

with the Cagneys, Robinsons and Bogarts. There was just so

much restorative entertainment to be had reminding ourselves

that crime didn’t pay. What was needed was something

accenting the positive -- the kind of buoyant affirmativeness

that made the rigors of competition and hardy individualism

easier to take even as they were being justified as cultural

premises. When you have a social outlook that often resembles

making it up as you go along, the glib isn’t that far

removed from the patriotic.

It

wasn’t a glibness completely synonymous with fantasies

about the posh and the luxurious, the way ‘white telephone’

screen melodramas were meant to divert audiences from the

daily grimness of Mussolini’s Italy. Although plenty

of Hollywood comedies were set in mansions and gave steady

employment to actors adept at playing butlers, humour was

a first democratic principle endemic to every class setting.

Millionaires were funny, hobos were funny, even gangsters

fired off cracks as regularly as their .38s. Many of the most

popular or accomplished pictures from the period -- My Man

Godfrey, Sullivan’s Travels, the Thin Man series --

rounded up all the classes for their jokes. Hitler had his

Nuremberg rallies, the United States had neighbourhood movie

theaters on every corner from New England to California.

Expropriation

of some universal human quality for a claim of cultural primacy

is nothing new; the function of propaganda has always been

to dehumanize the enemy in one way or another. In the particular

case of the 1930s and 1940s, there might have been no refuting

the enemy’s efficiency (Nazi), zealotry (communist),

or recklessness (anarchist), but without that leavening ability

to laugh at himself as much as at others, he (or she, if she

was Ninotchka) was a loser. As long as there was humour in

one’s makeup, even despair (a constant in the Capra

films) turned out to be a temporary aberration. Humour crystallized

the whole man, the completely committed man, the victorious

man. It was from the hierarchy of divine blessings. One ideology

was indeed more inclusive than the rest -- and would have

the armies, foreign aid and gross national product to prove

it for decades to come. He who laughed most laughed last;

he who laughed least didn’t last.

Which

should make us wonder about the ideological significance in

more recent times of resorting to laugh tracks.

Also

by Donald Dewey:

Cartoon

Power